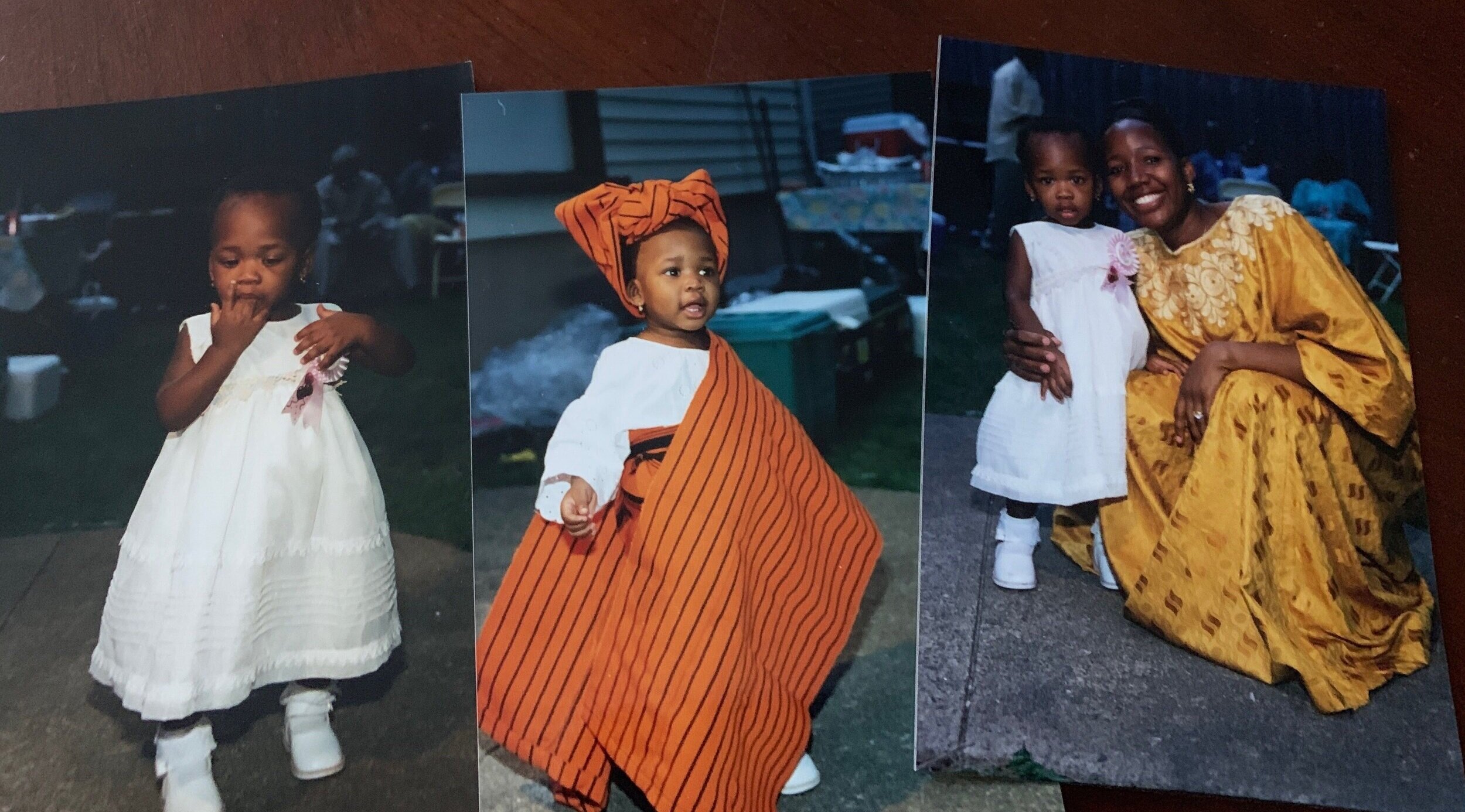

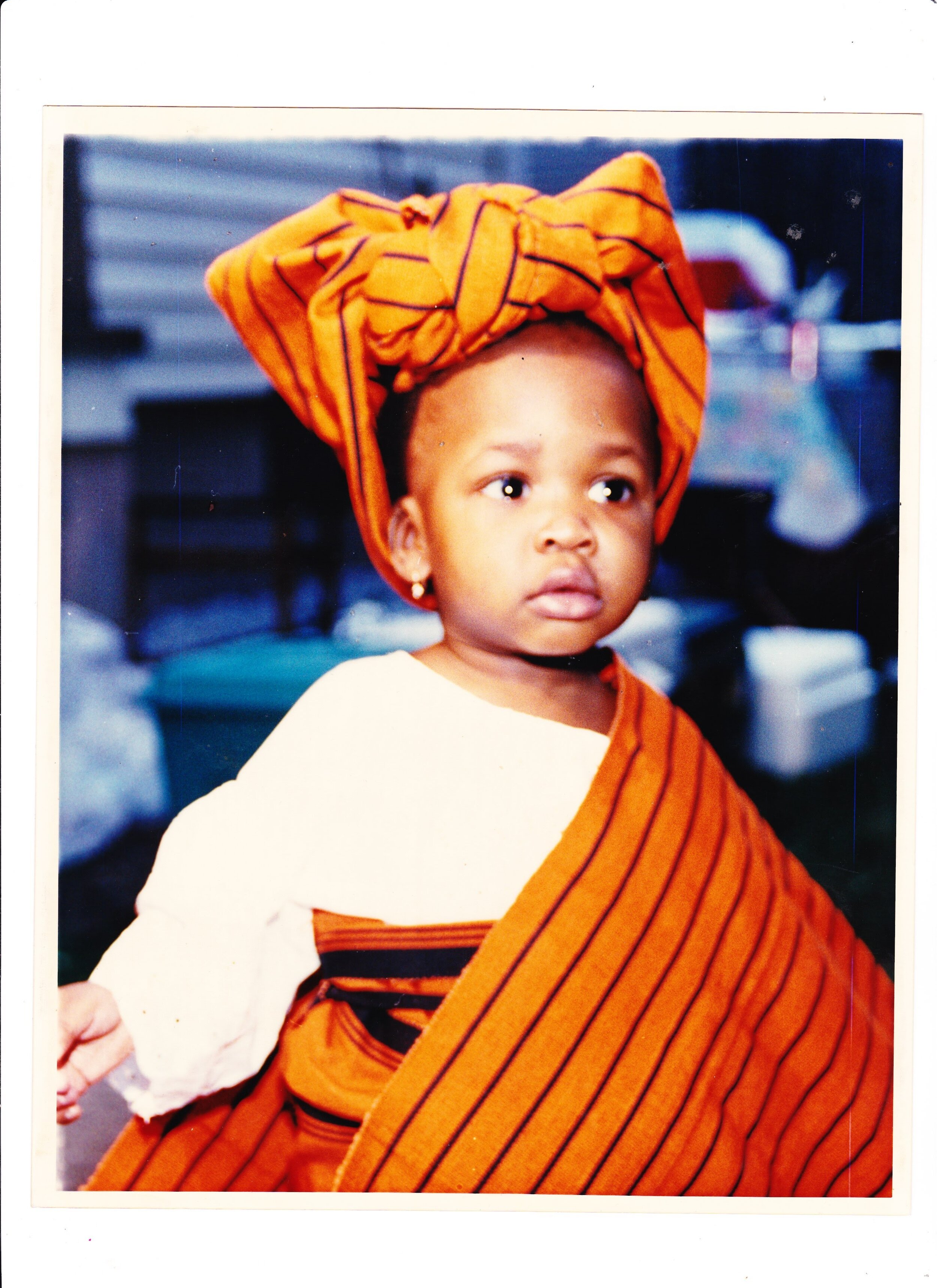

Caught Between Two Worlds: A First-Generation American’s Story

Photos courtesy of Hafeezat Bishi

By Hafeezat Bishi

Growing up, I was very proud of my heritage. I remember in preschool we made magnets for Father’s Day and I wrote “#1 dad from Nigeriya” on mine. Obviously, that isn’t how it’s spelled and I fixed it a couple of years later, but it’s a testament to the fact that ever since I was a child, my parents never let me forget where my roots came from.

My parents came to the United States to study—to gain an education that would help them get a better life. My dad, despite having the intention of going back to Nigeria after school, ended up staying here where he met my mom, and here I am nearly 20 years later. I was born in a country different from theirs, but I’m still made up of the experiences they brought over.

In elementary school, I met a girl who was also Nigerian, and we bonded over the fact that we came from the same tribe, ate the same food, and understood the same language. We always greeted one another with the little Yoruba phrases we learned from our parents and tried our hardest to perfect the Nigerian accents we didn’t have.

Photo courtesy of Hafeezat Bishi

To us, that was enough. It was exciting meeting someone who could relate to having that background, especially since we were two of the few Nigerians in our town. If anyone needed to know anything about Nigeria, we were seen as reputable sources.

However, it turns out I knew less than I thought. Yes, I ate authentic food, my parents played the old-school music in the car, and I had the traditional clothes. But to those back in our home country, that didn’t qualify me as “fully Nigerian.”

When I was in spaces that were primarily made up of West Africans, or Africans in general, having to tell someone I was Nigerian and Yoruba would bring embarrassment. They would say a greeting in Yoruba and while I understood, I would reply in English because it was the only way I knew how. I would get weird looks and get asked why I didn’t know my native tongue. I would tell them to ask my parents—I didn’t know why I couldn’t say more than five phrases either.

This was a complete contrast to being surrounded by my American friends who would grasp onto the few words I knew in amazement. It was an in-between feeling I couldn’t figure out because I felt alone in this feeling.

When I started university, I would gladly boast my Nigerian identity, in hopes of gaining recognition and acceptance into a group that I had never found myself in. But I didn’t listen to the music and I barely spoke the languages. And while they were “my people,” there was still a part of me grasping for something.

I remember introducing myself to another Nigerian on campus. When they realized I was born here in the states, they said, “Oh, so you’re not really Nigerian.” Although I’m sure they had no malintent, it still hurt to have part of my identity invalidated simply because I wasn’t born on the same soil.

Because of experiences like that, there was a part of me that tried too hard so no one could tell me I wasn’t Nigerian. Here I was, an adult, still trying to find a place where my identity would be taken as is and wondering if it would get better.

Thankfully, I’m now in a place where I recognize that I am enough and that my identity can’t be dictated by anyone but me.

I connect to my Nigerian culture by learning to cook the food my mother makes and listening to the stories of my father’s youth. I partake in American culture every day, from attending college sports games to partaking in the scary tradition that is Black Friday.

I am Nigerian, I am American, I am a Nigerian-American. I’m a girl from two parts of the world—both equally a part of her, both equally belonging to her.

I know where my roots stem from, the journeys my parents took that allow me to be here, and I will not be questioned for it.